Currents

In this section, we discuss:

- Causes of Currents

- Rip Currents

- Longshore Currents

- What are the three main causes of currents?

- What are some visible signs of a rip current?

- What is the important procedure to follow before entering the water where a longshore current is present?

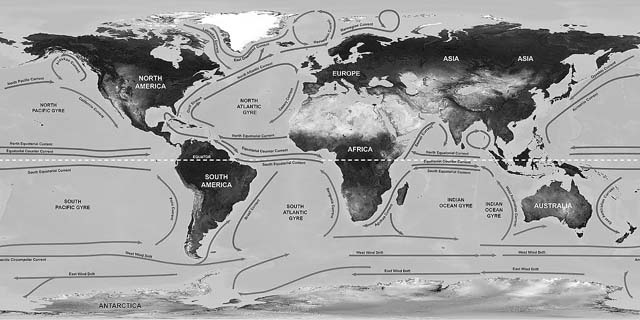

Causes of Currents

Currents can be caused by winds blowing over the surface of the water, tidal movement and waves. Sometimes a current is weak and widespread; sometimes a current can be strong and localized. Currents, when present, always affect how you dive.

The majority of currents are caused by wind, tidal movement and waves. Currents caused by winds blowing over the surface of the water are usually temporary. The strength of a wind-generated current will depend on the duration and force of the wind. Tidal movement can produce currents or strengthen an existing current. Undertow or rip currents occur when a wave breaks along a shoreline and the water rushes back into the ocean.

The direction and speed of ocean and coastal tidal currents vary depending on the time of the year, tide phases, bottom contours, water depth, and weather. Published tide and current tables only list possible conditions on the surface. The direction and speed of any currents under water will probably be different.

Rip Currents

You can recognize a rip current as a line of foamy water on the surface moving away from and extending beyond the surf zone. The water is usually dirty and there is no surf visible in the area due to the force of the water rushing seaward.

When a series of waves crashes on a coastline and the frequency between each wave is short, water can “pile up” on the beach. When the “pile” gets too high, the water rushes back out. If there is nothing in the way, the water rushing out creates an undertow as it travels back out to sea.

If obstacles, like sandbars, are in the way, the water is sometimes channeled between these obstacles creating a localized current rushing at potentially high speeds back out to sea. This is called a rip current.

If you get caught in a rip current, don’t attempt to swim against it. Swim perpendicular to the current until it subsides and you can swim to shore. Rip currents are localized and typically short in duration.

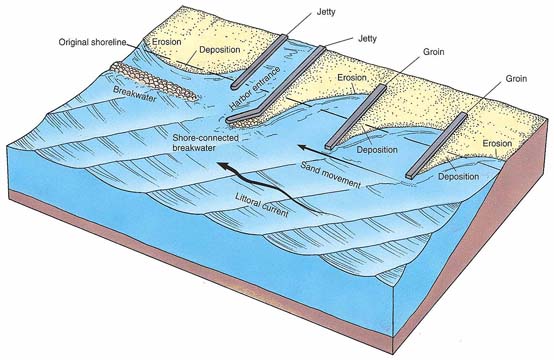

Longshore Currents

Waves seldom hit the beach head-on; they almost always do so at an angle. When this happens, the segments of the waves that hit the beach first slow down. The remaining segments of the wave “bend” and conform to the shape of the shoreline. As each segment makes contact with the shore, it releases energy that generates a current that runs parallel to the shoreline. This is called a longshore current.

When conducting a shore dive where a longshore current is present, you should evaluate water movement by observing swimmers, objects floating in the water or wave tops to determine the speed and direction of the current. This will help you choose optimal entry and exit points.

Most of the time, you will want to enter the water upstream from your planned exit point. You will also need to make allowances for how much the current will move you as you swim out to and back from the dive site. Remember to swim perpendicular to the current and not against it.

Key Points to Remember

- Currents can be caused by:

- Winds blowing over the surface of the water

- Tidal movement

- Waves

- A rip current can be recognized by:

- Foam on the surface extending beyond the surf zone

- A stream of dirty water extending away from shore

- No surf where the current has flowed toward the open water

- When conducting a shore dive where a longshore current is present, you should evaluate water movement by observing swimmers, objects floating in the water or wave tops to determine speed and direction of the current so that you can choose optimal entry and exit points.

Learn More on Wikipedia